Lessons in resilience at the University of Richmond

RESEARCH & INNOVATION

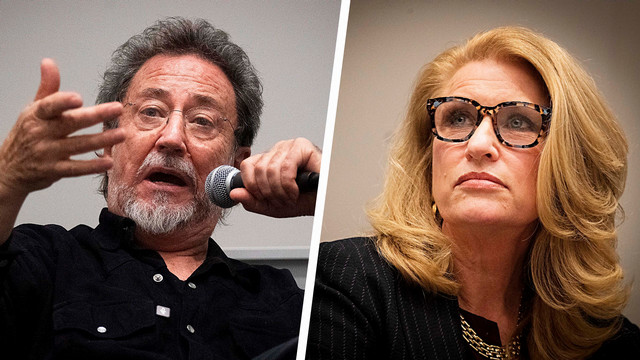

Mexican businessman Eduardo Valseca recounted his terrifying experience of being confined to a tiny concrete and wooden construct for seven and a half months after he was kidnapped around 19 years ago in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. He shared his story with behavioral neuroscience professor Kelly Lambert at a December event in Jepson Hall. The talk, The Resilient Brain: How the Mind Survives the Unthinkable, was moderated by author and neuroscientist Daniela Hernandez.

Valseca, whose story was covered by Dateline in “The Desperate Hours” and “The Ranch” episodes, was on campus to discuss how the brain responds to captivity, fear, and uncertainty.

Lambert covers Valseca’s gut-wrenching survival story in her upcoming book, Wild Brains, scheduled to be published this year. The book looks at her research on animals in the wild, including mouse lemurs in Madagascar, an important species for studying Alzheimer’s. In the last chapter, she explores the effects of captivity on the human brain, such as those experienced by Valseca and prisoners in solitary confinement.

When asked how much room he had to move in the box, Valseca indicated a tiny space using his thumb and index finger.

“Two inches above my head, and on each side,” he said.

“How does the brain survive?” Lambert questioned the packed, hushed auditorium.

Living through the unimaginable

When Lambert learned about Valseca’s story, she knew she had to talk to him. “It made me wonder what a human brain does when all elements of the external environment are stripped away, and one’s internal world is distorted with loud music, bright lights, terror, torture, an inability to speak, and no personal freedom.”

Valseca and his wife, Jayne, were ambushed in 2007 after dropping their children off at school. The captors released Jayne, but took Valseca to another location. He lived in the box, naked, with food, water, and a bucket for toileting brought in each day. He was regularly tortured, including being shot in the arm and leg. His kidnappers crudely stitched up the wounds with a needle but no anesthetic. Loud music played night and day.

Senior biology and cognitive science major Andrés Mauco (center), who works in Lambert’s lab, met Valseca after the panel. “I thanked him and told him that he was an inspiration.”

“You can only take so much. I was very strong and positive and dreaming that I was going to come out of this situation, but the pain is so strong, day after day, week after week, month after month. Then you start giving up. You reach a point, when you think, I don't think I can last longer,” Valseca recalled.

When his captors finally released Valseca, he was 80 pounds — half his normal body weight. His body had atrophied from lack of exercise, and he fell after taking two steps. It took him a while to get used to open spaces. At night, he rolled off the bed.

His symptoms have subsided with therapy. Today, Valseca appreciates each day and being free. “I love to see the sunrise and the sunset,” he said. “I don’t care if it’s raining, I still get out for a walk.”

Keys to survival

During his time in captivity, Eduardo didn’t have a phone, books, or any type of distractions. He repeated mantras endlessly each day to make it through boredom and torture.

“The first thing that I said to myself was, ‘I am in control of myself. These guys are not in control of me,’” Valseca remembered. “And the second thing that I said, thousands of times a day, was, ‘Trust the universe.’”

As he thought those words, Valseca visualized the stars at night, bright and spread out over the dark sky above his ranch. He thought about being part of this magnificent creation.

He often pictured his wife and three young children. “And then I would say, ‘Love can go through anything,’” Valseca recalled. “And that’s where I got the fuel with these three simple things that I felt deep, deep, deep in me. They kept me going.”

According to Lambert, Valseca’s mantras and visualizations were important for keeping his brain functioning and reducing chronic stress levels.

“Eduardo’s case provides an example of how someone can survive unthinkable conditions and maintain mental health after the event. His coping strategies during his captivity may inform future research in this area,” she said.

The brain’s ability to adapt and recover

Lambert’s research focuses on experience-based neuroplasticity, the brain’s extraordinary ability to rewire itself to allow it to learn, adapt, and recover from injury or extreme threat. According to Lambert, wild rats develop greater neuroplasticity than those living in a laboratory setting.

“The laboratory-enriched environments are similar to a rodent Disneyland. The wild, however, is more like living in a Survivor episode — both enriching and threatening, requiring sophisticated response strategies just to survive,” she said.

Studying animals living in challenging, dynamic environments is critical to giving an authentic picture of what brains can do and may yield important lessons for humans, she reasons in Wild Brains.

Lambert is encouraged by the plasticity and resilience she sees in the natural world. “Our ancestors survived a lot,” she said. “I think we probably have more capacity for resilience and hope and survival than we think we do.”