'The miracle is never lost on me'

Alumni

As a high school senior, Brian Merkel looked forward to attending the University of Richmond in the fall. Then his life changed on Mother’s Day weekend, 1984.

On Friday, he noticed a rash on his ankle. He hadn’t been feeling great all year, something he chalked up to not playing his usual sports. Being extra cautious, he decided to see a dermatologist.

“I just thought I was going to get some cream and go home,” Merkel said. “As a teen, the last thing you’re going to think is that you have leukemia.”

By the end of the weekend, he began chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia, a fast-growing cancer of the blood and bone marrow. The disease causes excess immature white blood cells to form, which interfere with normal cell development. What he had thought was a rash was instead a series of pinpoint bruises known as petechiae — often a sign of leukemia.

His distraught mother bought him eight pairs of flannel pajamas for his hospital stay because she didn’t know what else to do. Doctors said his only chance of survival was a bone marrow transplant; with the transplant, it was only 10 percent. At the time, he said, only two places in the world were having any success with the procedure, then in its infancy. The New Jersey family packed their bags for one of them, Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson’s Cancer Research Center.

His sister served as his donor. The transplant had complications, and at one point he was near death and in kidney failure. Merkel, an inpatient for four months, deferred his college enrollment.

But a year later, still medically frail and taking powerful immunosuppressants, he began his freshman year at UR in fall 1985 determined to have a normal college life. “When I went off to college, I just wanted to be like everybody else.”

Merkel felt drawn to science classes because of his condition. “I had to figure out and learn more about the things that were going on with me and why things happened the way they did.”

He joined a fraternity and made close friends there, as well as through his science classes. “There were a lot of good people that I met at the University of Richmond,” Merkel said. “When I think about all the places I could have been, and dealing with everything I was dealing with at the time, it really was a great place for me to be.”

His mentors included the late Professor Francis Leftwich, then chair of the biology department. Sitting in his office one day following graduation, “I remember thinking, `What a great way to live, that you have the chance every single day of your life to do something meaningful for students.’”

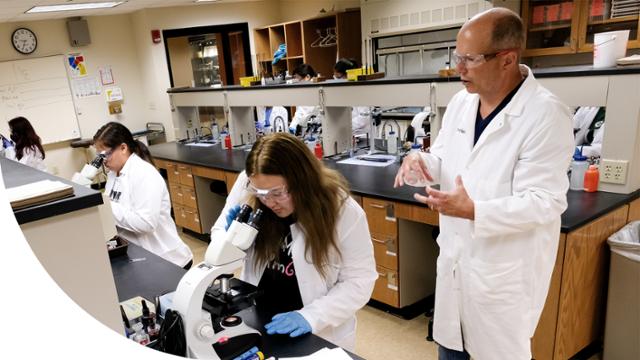

After graduating with the Class of 1989, Merkel went on to receive his Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology at VCU. Today he is the chair of human biology at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

His research includes information literacy, the effects on environmental toxicants on immune function, and the impacts on the immune system by the herbal supplement, Echinacea. He and his students are also involved in the Tiny Earth Curriculum, an international project devoted to solving the crisis of antibiotic resistance through the help of student investigators. “Over 14,000 students every single year, around the world, are looking for antibiotic producers in the soil,” Merkel said.

For many years, he did not share his story. But today sees it as a strength. “I’m a living testament to the power of science,” he said. “Every day I think about this: Given my prognosis, a 10 percent chance of living, that I am now a chair of a program in human biology, the miracle is never lost on me.”