If you want to visit the most forward-looking places on campus, the Queally Center for Admission and Career Services is a good place to start. In its hallways, suit-clad juniors and seniors awaiting interviews pass wide-eyed high school students on the college-search circuit. Everyone at Queally, in one way or another, is looking at what the future holds.

For this reason, Queally was a fitting if not obvious place for a November gathering marking a moment of university history. In the fall of 1968, the university’s first three African-American undergraduate alumni began their first semester on campus: Barry Greene, Isabelle Thomas LeSane, and Madieth Malone, all 1972 graduates.

The trio sat front and center among an audience of several hundred as speakers thanked them for exemplifying, in the words of Mia Reinoso Genoni, Westhampton College dean, “how courage is both an everyday act and an extraordinary achievement.”

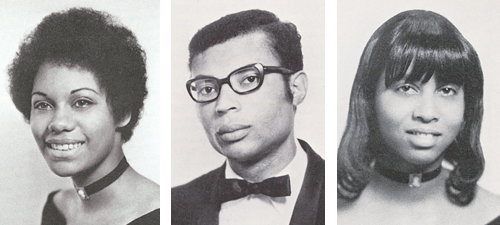

Malone, Greene, and LeSane in 1972.

Although the dean was speaking specifically of the Westhampton alumni, her remarks applied to all three when she added, “[They] had the ability to look beyond the university’s past limitations and see it as it could be — and help shape it — along with those classmates, faculty, and staff who chose to welcome them at a time when not everyone did.”

The university had first admitted African-American students just a few years earlier, and done so unenthusiastically. It restricted admission to specific evening programs, including one that the university had taken over from the U.S. Logistics Center and Quartermaster Service at Fort Lee. One of these students, a civilian Fort Lee employee named Walter Carpenter, became the university’s first African-American graduate when he completed his master’s degree in commerce in 1964. In response to questions about the new policy, the university issued a statement declaring that “no further integration is contemplated.”

Four years later, Greene, LeSane, and Malone stepped onto campus. LeSane and Malone commuted, and Greene, as he recounted in the Autumn 2018 issue, was a residential student. They earned their degrees in Russian studies, theater arts, and biology, respectively.

At the Queally event, the speakers’ desire to express gratitude was equalled by their determination to connect this moment from the past to the university’s present and future. In her remarks, Alicia Jiggetts, ’19, an African-American student, was straightforward: “Had they not [chosen to come to Richmond] 50 years ago in the fall of 1968, I would not be speaking to you now as a senior in the fall of 2018.”

Jiggetts then pivoted forward. “The University of Richmond, like me, is still on a journey,” she said, “constantly moving forward, facing obstacles, and occasionally needing to pause and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses.”

Following her remarks, Ronald Crutcher, president, announced the formation of the Presidential Commission on Institutional History and Identity to examine how the university records, preserves, and communicates its history.

In doing so, he had in mind, he said, “Spiders yesterday, today, and tomorrow.”